By Kellie Woodson

As an instructional designer, I use my expertise in teaching and learning to create learning experiences on a wide variety of health topics. Whether I’m developing a course on breast cancer genetics or oral health , a significant part of the process is partnering with experts in the field to develop courses that are informative, engaging and effective. Since many of these courses are written for frontline health workers such as community health workers or promotores (CHWs/Ps), they must also motivate participants to make positive changes in their communities.

[RELATED: Improve the mental wellness of your team]

Overcoming Barriers to Healthy Choices

A typical course not only provides information on health conditions; it also teaches strategies to effectively guide others in making healthier choices. To do this, it is important to acknowledge the barriers to healthy living that many people face.

For example, we know that regular health checks and healthy eating are important to overall health. But the truth is, getting to the doctor or grocery store can be very difficult for individuals who are disabled, elderly, or who live in rural areas.

The courses I write challenge participants to acknowledge and reflect on the realities of others that they might otherwise take for granted.

- How does a person who struggles to get around their own home travel to regular doctor’s visits?

- How can a person make healthier food choices if they only have access to neighborhood convenience stores?

- Does the disproportionate number of tobacco advertisements in low-income communities affect smoking rates in these areas?

- How does one’s education level affect their ability to complete an application for financial healthcare assistance?

The truth is that for many individuals, factors such as age, disability, geographical location and education level pose significant barriers to staying healthy. These barriers in turn give rise to health disparities, or preventable differences in the rate of disease and access to health services among specific groups of people. While health disparities can and do affect all people, they are more common among minorities and the socio-economically disadvantaged.

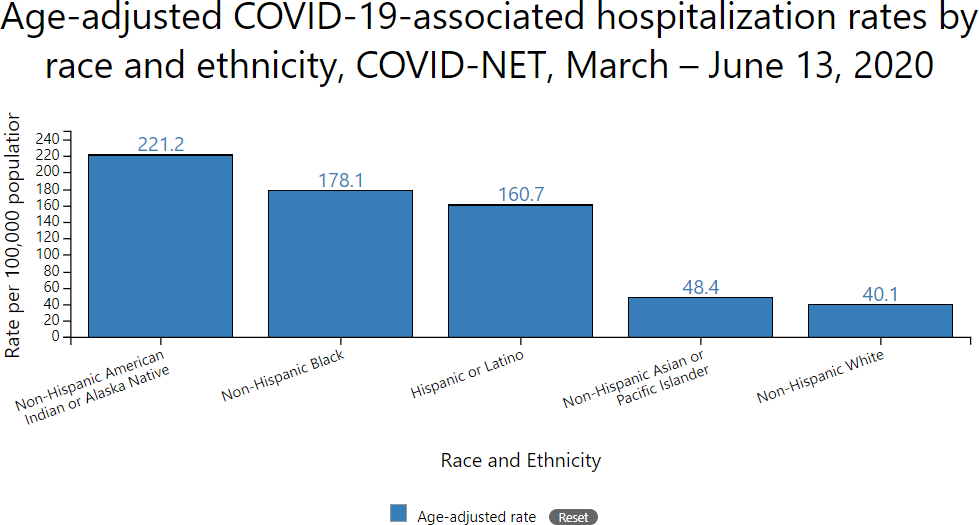

The coronavirus has been a wake-up for many as they see how the pandemic is affecting races differently in this country. Hospitalization and death rates from COVID-19 are highest among American Indian or Alaska Native and non-Hispanic blacks—five times higher than for whites, according to the CDC.

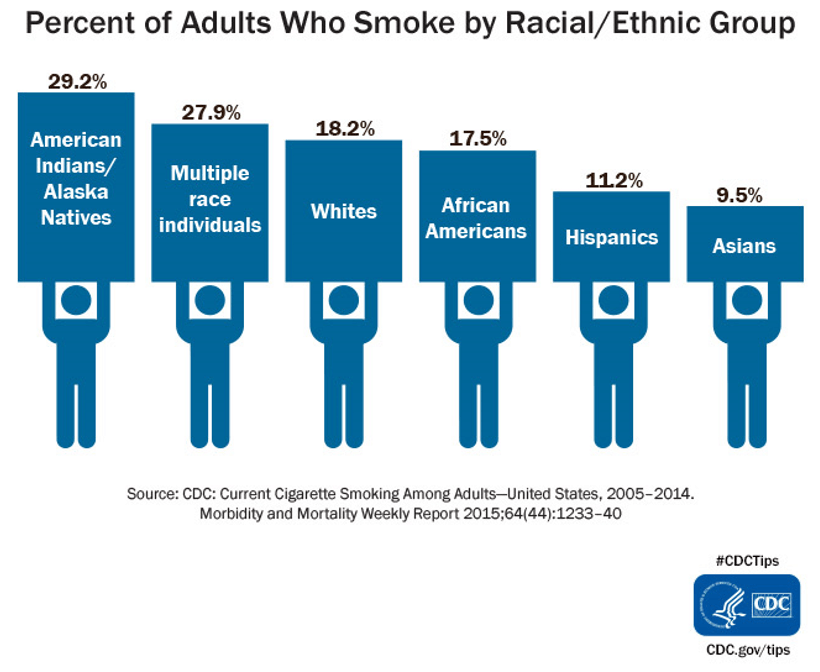

When writing a tobacco cessation course for the state of Washington’s Community Health Worker Training program, I learned that African Americans, Asian Americans, members of the LGBT community and American Indians use tobacco products in disproportionate numbers when compared to other groups in Washington.

Across the nation, individuals with lower income and education levels are also more likely to use tobacco. These disparities then give rise to tobacco-related illness and disease. Due to the lack of quality health care, individuals living in rural areas, those who are living at or below the poverty line and those who have lower education levels are more likely to die as a result of tobacco-related disease.

Health Disparities Reach Farther Than You Think

It’s important to understand that health disparities aren’t simply the result of groups of people making bad choices. Disparities are systemic, complex and cyclical in nature. For example, groups of people who migrated to the U.S. have been found to have high rates of mental disorder and trauma due to the hardships they experienced during migration. Racism and oppression often result in trauma-related mental illness. To make matters worse, marginalized groups of people often avoid diagnosis and treatment which further perpetuates these disparities.

Consider these statistics:

- Asian-American women over age 65 have the highest suicide rate of all similarly-aged women in the United States.

- LGBT youth are about 2 1/2 times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers.

- Only about ten percent of physicians practice in rural America.

- People who live and work in low socioeconomic circumstances have an increased risk for mortality, unhealthy behaviors, reduced access to health care and low quality of care.

- Due to trauma experienced before and after immigration to the United States, Southeast Asian refugees have an increased risk for posttraumatic stress disorder.

- Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are 30 percent more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than whites.

- Close to a third of Hispanics get regular health care, including those with chronic health conditions.

- African-American adults with cancer are significantly less likely to survive prostate cancer, breast cancer and lung cancer than their white counterparts.

These alarming statistics only represent a small fraction of the disparities that exist in our country. Remember that health disparities are found in every group in the U.S. and in every part of the body.

Frontline Health Workers and Communities

Being a frontline health worker is not just about giving guidance and advice– it’s a call to action and advocacy. These people and their employers their community members better than anyone else, and they understand the communities’ challenges, weaknesses and strengths. As they educate and guide clients to achieving better health, they have the responsibility to acknowledge barriers to care and why they exist. This understanding will help them to better anticipate their client’s needs and respond appropriately and effectively.

Frontline health workers take different paths to solving problems. Many take it upon themselves to create much needed resources and programs in their communities. Others see themselves as organizers who unite members of the community to create solutions where none exist. Whatever the response, you are in the position to make a tremendous impact.

At the end of the day, the goal is to build communities where race, sex, sexual identity, age, disability or socioeconomic status never, ever affect one’s ability to be healthy.

Kellie Woodson is an expert in teaching, learning, and instructional design with content area specialization in health, science, and mathematics. She has extensive experience developing curriculum and learning programs for schools, organizations, and national and international publishers.